From Kyivan Rus’ to the Modern State: Forgotten Milestones in Belarusian History

Introduction

- Introduction

- The Origins: Belarusian Lands in Kyivan Rus’

- The Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Belarusian Language

- Belarusian Nobility in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

- Imperial Russia and the Loss of Autonomy

- The Belarusian People’s Republic (1918)

- The Soviet Era: Repression, War, and Reconstruction

- Postwar Belarusian Identity in the USSR

- Independence and the Birth of the Modern State (1991)

- Forgotten Milestones and Historical Memory

- Belarus in International Historiography

- Conclusion

The history of Belarus is often overshadowed by the narratives of larger regional powers such as Russia, Poland, and Lithuania. Yet the story of Belarus stretches back more than a thousand years, shaped by complex political, cultural, and linguistic developments that challenge simplistic stereotypes. A close examination of “From Kyivan Rus’ to the Modern State: Forgotten Milestones in Belarusian History” reveals a layered past rich with transformation, resistance, and cultural evolution.

This article explores the crucial but often overlooked milestones that shaped Belarus’s identity—from the early medieval era of Kyivan Rus’, through the cultural flourishing of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, to the struggles for independence in the 20th century and the political realities of the modern state.

By illuminating these forgotten chapters, we gain a clearer understanding of Belarus not as a passive borderland, but as a nation with deep historical agency whose experiences continue to influence its present and future.

The Origins: Belarusian Lands in Kyivan Rus’

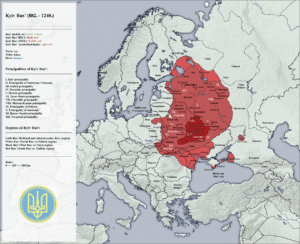

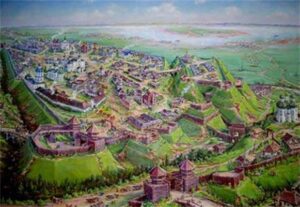

The earliest historical records of Belarusian territory date back to the period of Kyivan Rus’ (9th–13th centuries), a medieval East Slavic state centered around Kyiv. The lands of modern Belarus were home to powerful principalities such as:

- Polotsk – one of the most influential early Slavic political centers

- Turaŭ (Turov) – an important religious and cultural hub

- Mensk (Minsk) – emerging by the 11th century as a strategic settlement

The Principality of Polotsk, in particular, played an outsized role in shaping early Belarusian identity. Ruled by the Rurikid dynasty, Polotsk often acted autonomously from Kyiv, forging its own political alliances and cultural traditions.

The era saw the development of early East Slavic writing, Christianization, and the foundation of ecclesiastical centers. Scholars studying Slavic medieval history can find archival material through databases like JSTOR.

While modern narratives sometimes conflate Belarusian history with broader Russian or East Slavic history, the distinctiveness of Polotsk and Turaŭ shows that Belarusians have deep historical roots predating later imperial structures.

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Belarusian Language

After the Mongol invasions, Belarusian lands became part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (GDL), beginning in the 13th century. Far from being a conquered territory, Belarusian elites played a central role in the political and administrative life of the GDL.

One of the most fascinating and forgotten milestones is that the official state language of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania during the 14th–16th centuries was not Lithuanian—but Old Belarusian (Ruthenian).

This language served as:

- the language of the legal code (Statutes of the Grand Duchy)

- the language of the chancery

- a common administrative and diplomatic tongue

This demonstrates a remarkable fact: during this era, Belarusian culture enjoyed a level of prestige and institutional power unmatched until the contemporary period.

During the GDL period, cities like Brest, Grodno, and Polotsk thrived as centers of commerce, religious diversity, and intellectual life.

Further historical background on the GDL can be explored through public resources like Wikipedia.

Belarusian Nobility in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

In 1569, the Union of Lublin formed the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, one of the largest and most multicultural states of early modern Europe. Belarusian lands remained important within this vast political entity.

The Commonwealth period fostered:

- Religious pluralism (Orthodox, Catholic, Uniate, and Jewish communities)

- Cultural renaissance tied to the printing revolution

- Growth of noble self-governance through the szlachta class

Figures such as Francysk Skaryna, a pioneer of Eastern European printing, embodied Belarus’s cultural contributions to the region. His Belarusian-language Bible (1517) is celebrated as one of the earliest books printed in any Slavic language.

Belarus’s role in the Commonwealth complicates modern distortions that reduce Belarusian history to a sphere of Russian influence. Instead, the region served as a bridge connecting Western and Eastern Europe.

Imperial Russia and the Loss of Autonomy

Following the partitions of the Commonwealth (1772–1795), Belarusian lands were absorbed into the Russian Empire. This marked a turning point, as policies of russification began eroding local autonomy.

Key features of this era included:

- Suppression of the Belarusian language in public life

- Conversion campaigns targeting the Uniate Church

- Heavy taxation and economic restructuring

- The rise of anti-imperial uprisings (1830–31, 1863–64)

One of the most significant rebels was Kastuś Kalinoŭski, a revolutionary whose writings in Belarusian inspired later national movements. He remains a symbol of anti-imperial resistance in Belarusian memory.

This era also witnessed broader social and economic changes, including the gradual decline of serfdom and the emergence of new urban centers.

The Belarusian People’s Republic (1918)

Amid the chaos of World War I and the Russian Revolution, Belarusian national activists declared the Belarusian People’s Republic (BNR) on March 25, 1918. Though short-lived, the BNR is a milestone of immense symbolic significance.

The BNR represented:

- the first modern Belarusian state project

- attempts to establish democratic institutions

- the assertion of Belarusian cultural autonomy

Today, Belarusian opposition movements celebrate March 25 as Freedom Day, honoring the legacy of the BNR. Exiled activists maintain institutions linked to the BNR to this day.

Historical records related to the BNR and its leaders can be explored through digital archives hosted by research institutions like the Library of Congress.

The Soviet Era: Repression, War, and Reconstruction

Belarus was incorporated into the Soviet Union as the Byelorussian SSR, a state that experienced dramatic transformations, including industrialization, collectivization, and repression.

The Soviet period includes several critical yet often overlooked milestones:

- Stalinist purges that devastated Belarusian intellectuals and elites

- Forced deportations and political repression

- The Holocaust and Nazi occupation, during which Belarus lost a quarter of its population

- Postwar reconstruction that reshaped the demographic and social landscape

Belarus became one of the most heavily affected territories during World War II. Entire villages were destroyed, and the Jewish population was nearly annihilated. The memorial complex at Khatyn stands as a symbol of this trauma.

These experiences forged a unique collective memory, influencing Belarus’s postwar identity and its reverence for “the Great Patriotic War.”

Postwar Belarusian Identity in the USSR

After 1945, Belarus underwent rapid modernization. Cities like Minsk were rebuilt from ruins into modern Soviet centers. The state fostered a Soviet Belarusian identity that blended local traditions with socialist ideology.

However, this era also saw:

- a decline in Belarusian-language education

- urbanization that diluted rural cultural traditions

- the emergence of new Belarusian artistic movements

Belarusian literature and arts thrived despite censorship, with authors like Vasil Bykaŭ gaining international recognition for their war narratives.

Independence and the Birth of the Modern State (1991)

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, Belarus declared independence on August 25, 1991. This marked a new chapter in Belarusian history—one filled with both opportunity and conflict.

Key developments include:

- Establishment of Belarusian democratic institutions

- Restoration of national symbols like the white-red-white flag

- Creation of Belarusian-language educational programs

- Adoption of a market economy

However, the 1994 election of Alexander Lukashenko initiated a political shift toward authoritarianism. Many democratic reforms were reversed, and Soviet symbols and narratives reemerged in state propaganda.

Despite this, the legacy of Belarusian independence lives on in civil society movements, cultural activism, and the 2020 protests, which demonstrated nationwide desire for democratic reform.

Forgotten Milestones and Historical Memory

The theme “From Kyivan Rus’ to the Modern State: Forgotten Milestones in Belarusian History” highlights how selective memory has shaped public understanding of Belarusian history. The state often emphasizes certain periods (such as the Soviet era) while downplaying others, especially:

- the role of Old Belarusian language in the GDL

- the democratic aspirations of the BNR

- Belarusian participation in 19th-century uprisings

- the multicultural heritage of the Commonwealth era

Independent historians and activists continue working to restore these forgotten narratives, publishing research, documentaries, and digital archives. Their work contributes to a broader revival of Belarusian identity.

Belarus in International Historiography

Internationally, Belarusian history is gaining increasing scholarly attention. Historians now emphasize the unique historical path of Belarus as distinct from both Russia and Ukraine.

Think tanks such as the Atlantic Council and academic institutions across Europe and North America have begun publishing new research, highlighting Belarus’s role in regional geopolitics and cultural history.

This broader engagement helps challenge misconceptions and bring Belarusian voices into global discussions.

Conclusion

Exploring “From Kyivan Rus’ to the Modern State: Forgotten Milestones in Belarusian History” reveals a long and complex journey marked by resilience, cultural innovation, and political upheaval. The Belarusian people have navigated centuries of shifting powers while preserving their distinct identity, language, and traditions.

From medieval principalities to modern independence movements, from cultural renaissances to periods of repression, Belarusian history is far richer and more dynamic than simplified narratives admit. Understanding these forgotten milestones is essential not only for academic scholarship but also for the Belarusian people seeking to reclaim their past and envision their future.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.